Some Takeaways from my Time as a PhD Student

The big picture

Looking back on the last five years, I think I had about as good of an experience doing a PhD as one can have.

That’s not to say that everything was rainbows and unicorns. Major sources of stress over the years included facing challenging course material, learning how to balance the demands of teaching with my other responsibilities, running into countless dead ends in a research project, soul-searching about what kind of career I wanted to pursue, and navigating the uncertainty of the job search. I suspect that both chronic and acute stress contributed to several prolonged illnesses I had during this time frame.

But on the whole, grad school was a good experience. I learned a lot (about topics both expected and unexpected), met many interesting and inspiring people, and now feel prepared (to the extent one can be) for embarking on my post-student chapter.

A lot of standard advice for being a PhD student served me well:

- Picking an advisor (or advisors) who you “click” with as a person, in addition to being aligned with on research interests;

- Prioritizing your dissertation research (getting it done) above all else;

- Taking the opportunity to explore, pushing yourself outside your academic comfort zone;

- Developing / refining soft skills (writing, oral presentation) in addition to technical skills;

- Getting plenty of sleep, nutritious food, and regular exercise, and staying in frequent communication with friends / family;

- Acknowledging the endurance nature of this endeavor, and taking ample time to rest along the way.

Here I’ll advocate for one less-standard practice that has also served me well.

Track your hours

When I started grad school in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, I tracked my working hours in a spreadsheet for curiosity’s sake. I continued this practice for the duration of my PhD for several reasons.

Early on, an upper-year student told me that if one was disciplined, it was possible to treat our PhD program like a 9-to-5. I chose not to stick to that rigid of a schedule, partly due to my preference for taking a break in the middle of the day to exercise and mentally reset, but I did use this perspective to guide the volume of hours that I worked, acknowledging that some weeks would be busier and others less busy due to factors outside of my control. Note: the number of hours per week needed to be successful as a PhD student varies with the discipline, as well as the individual. For example, research that requires bench work is often more time intensive than computational research. Similarly, an individual who enters a PhD program with a lot of relevant technical and/or domain knowledge will need to spend less time doing background reading than a student who is new to the field.

From the get-go I was interested in exploring careers outside of academia, while keeping the door to academia open. Through informational interviews and reading online, I learned that a number of jobs I might be interested in, such as research consulting, required one to track “billable” hours across projects. Hence, tracking my hours in grad school felt like good practice for potentially needing to do this later on. I have since learned that academic jobs too require a fair amount of documentation on the allocation of one’s time/effort, whether that be between research grants covering different fractions of one’s salary or between one’s research, teaching, and service responsibilities.

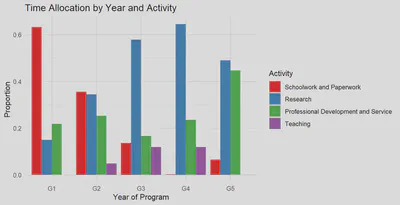

During grad school, I classified my working hours as either schoolwork, research, teaching, or professional development & service. The final category is somewhat nebulous. Major tasks I lumped into this include volunteering with career-relevant student organizations or on department committees, mentoring junior students, attending career development events, building my website and updating my CV and LinkedIn, networking / informational interviewing, attending scientific or public policy seminars not directly related to my research area, reading professionally-relevant newsletters, writing blog posts, and searching for and applying for jobs. Note: in the rest of the professional world, many of these tasks would not count as “working” hours.

Keeping track of approximately how much time I spent on each activity-category per day was helpful both in real time (e.g., deciding how much more work to do in a given week) and in retrospect (noticing bigger-picture patterns, appreciating how much time I’d put in the past semester). At my current juncture, having this record enables both creating interesting summaries like the following figure and making informed predictions for how much time it will take me to accomplish various tasks (and thus plan ahead) in my new job.

This plot shows the proportion of time I spent in each year of my PhD program on schoolwork & other necessary paperwork, research, teaching, and professional development & service. Note that these proportions represent the average for the whole year (academic year and summer), that the denominators for the five years are different (and I am intentionally choosing not to include those in this publicly available blog post), and that in my fifth year, the red bar represents the time I spent preparing to defend / graduate (putting together my dissertation document, preparing my defense slides, etc.).

Possibly the best reason to track your hours is to be able to assess alignment between how you are spending your time and how you should be or want to be spending your time. For instance, if you notice that you are consistently spending an unreasonably high number of hours per week grading or answering student emails for a class you are TAing, then it’s probably time to discuss this burden with the course instructor and/or update your approach. As another example, does the number of hours you are spending on a particular service or professional development activity align with how much you personally care about that activity and/or how important you think the activity is for your career advancement? (Speaking with people in your desired profession is often the best way to assess the latter.)

One last thing to clarify is that my system requires being honest with myself about how much time I am actually focused on work. For instance, if I get distracted and end up scrolling social media for 30 minutes, then I do not include that time in my work log. But, as I and others have found, being “on the clock” can help to maintain a work mindset (focus). Note that if instead of tracking your hours manually you would prefer to automate the process, then there are a variety of options you can explore, such as Toggl.

Caveat and parting thoughts

One caveat is that hours spent are only a proxy for effort. As you have likely experienced, different tasks require different amounts of energy. Being creative (brainstorming research ideas, writing a paper, creating curriculum) takes more energy than reading a paper (especially one which doesn’t require you to learn many new concepts) or grading a homework assignment based on a detailed rubric.

Ultimately, the most important thing during your PhD (and life in general, IMHO) is to be intentional. A hiking analogy for this is described in the first section of my earlier blog, “On Finding a Career Path”.

Recommended reading

- “So long, and thanks for all the tips” by Daniela Witten

- “A Few Lessons I Learned from My Ph.D. Program” by Tianyi Liu

- “Mimetic Traps” by Brian Timar – thanks to Apara Venkat for the suggestion

General resources for PhD students:

- “Uncovering the Hidden Curriculum” –> “Advice” section

- PhD student and postdoc resources collection – neuroscience focused, but many things are generalizable